Barbie is a young, single woman who lives in a house she owns. Let’s momentarily ignore the fact that her home is listed for $25 million exclusively on Trulia, and acknowledge that owning a house in the first place — “Dreamhouse” mansion or not — is very unusual for young women today. And it was even rarer when she originally became a homeowner in 1962. Looking back over the decades at how unusual Barbie is, demographically speaking, shows how broad social changes and the recent housing boom and bust have affected the living situations of young women.

Using U.S. Census data from 1960 to 2011 (the latest available; see note at end of post), we calculated the share of young women, aged 25 to 34, who are “living like Barbie” in that they:

- Are single and have no kids

- Are the “head of household” — Census-speak for the person who is named a home’s owner, buyer, or renter (as opposed to living in someone else’s home, like parents)

- Own their home (as opposed to rent)

- Live in a single-family detached house (as opposed to a townhouse or condo)

In 2011, 1.6% of young women shared Barbie’s living situation in all these ways. Here’s how we arrived at that. In the 25-34 year old age group, 31% of women were single and had no kids. Among these single women with no kids, approximately one-third were the “head of household.” The rest were living in someone else’s home (such as their parents). That means 11% of young women were single with no kids and the “head of household.” Of that 11%, approximately one quarter owned their home, and the rest rented. Among the homeowners in this group, a little more than half owned a single-family, detached house, as opposed to owning a townhouse or condo. That’s how we calculated that 1.6% of young women in 2011 had a living situation similar to Barbie.

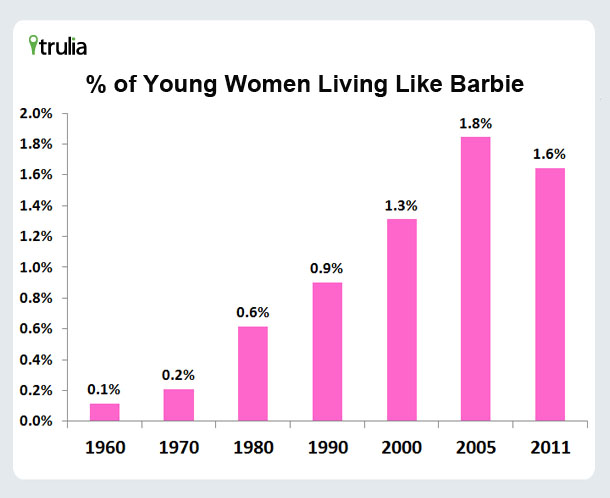

That may sound low, but the world has come a long way. Rare as it is today for young women to own a home, it was almost unheard of in 1960, one year after Barbie was introduced and two years before she became a homeowner. Back then, just 0.1% of young women owned a home – around one in a thousand. That means Barbie’s living situation was 15 times more common in 2011 than in 1960 – as the chart below shows.

What accounts for the huge changes over the past half-century? The biggest factor is the declining rate of marriage among young women. In 1960, just 8.3% of women aged 25-34 were single and had no kids, compared with 31% in 2011. Also, the homeownership rate among single young women with no kids grew significantly over these decades.

Although Barbie’s living situation has become much less unusual over the decades, check out the trend in the chart above: the share of young women “living like Barbie” actually fell a bit, from 1.8% in 2005 to 1.6% in 2011. That’s entirely due to the decline in the homeownership rate after the housing bubble burst. The share of young women who are single and without kids continued to rise from 2000 to 2011, but their homeownership rate has declined since 2006.

How different are young women from young men? Men aged 25 to 34 are almost twice as likely (3.1%) as women of the same age (1.6%) to “live like Barbie” – in the sense of being single with no kids, being the “head of household,” owning their home rather than renting, and living in a single-family house. What accounts for the gap between young men and young women? Several factors: young men are more likely to be single with no kids living with them, and more likely to be homeowners.

So what are the odds of living in a Barbie world? Few of us will live like Barbie, as a young single woman in a house she owns. But big social changes – like the shift toward staying single and the long-term rise in homeownership – puts Barbie’s living situation within reach for many more women today than at almost any other time since Barbie was introduced.

*Note: The analysis above was based entirely on decennial Census and American Community Survey data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS). “No kids” refers to not having one’s own children living in the household. The term “head of household” has been replaced by “householder” in recent Census surveys, but we’ve opted to use “head of household” for clarity. Full citation: Steven Ruggles, J. Trent Alexander, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Matthew B. Schroeder, and Matthew Sobek. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Machine-readable database]. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2010.