How fast have cities and suburbs grown recently? During last decade’s housing bubble, suburbs and rural areas grew much faster than cities. But briefly, early in the housing recovery, it looked like the long suburbanization of America might go into reverse. For a moment in 2011, urban counties grew faster than suburban and rural counties. Since then, old patterns have returned. Suburbs are now gaining population faster than urban neighborhoods, even though home prices are rising faster in cities than in suburbs. And the trend seems likely to continue. Trulia’s latest consumer survey and projected demographic shifts point to future headwinds for urban growth.

To compare cities and suburbs, we classify individual neighborhoods as urban or suburban based on whether or not most households live in detached single-family homes (see note on methods and data sources). This definition better reflects how residents describe their neighborhoods than do official city boundaries. That’s because many neighborhoods within big-city limits consist overwhelmingly of single-family homes and feel more suburban than urban.

Prices Rising Faster in Cities, but Population Growing Faster in Suburbs

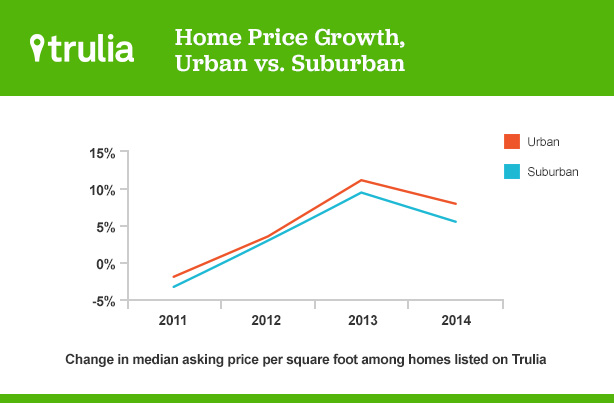

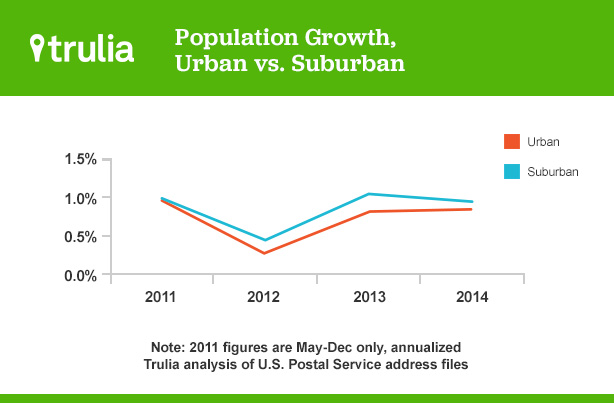

In the recovery, the home-price rebound has been stronger in urban neighborhoods. Most of the overbuilding during last decade’s bubble involved single-family suburban homes, and the single-family vacancy rate remains elevated. Comparing urban and suburban neighborhoods in the 100 largest metros over the past four years, urban home prices have consistently risen faster, or fallen less, than prices in suburbs. And, for the year 2014, the urban median asking price per square foot rose 8.1% versus a 5.7% gain in suburban neighborhoods.

However, during most of this period, suburban population growth has been faster than urban growth. In 2014, suburbs grew 0.96% and cities 0.85%, according to Postal Service data on occupied homes receiving mail. That’s not a huge difference, but it continues the trend of suburbs outpacing urban areas.

How can prices rise faster in urban neighborhoods even as suburbs lead in population growth? One reason is that most new construction takes place outside urban neighborhoods. Cities have less open land, and often more onerous regulations limiting new construction. It’s true that in 2014 multiunit buildings—typically located in urban neighborhoods—accounted for the highest share of overall construction since 1973. Still, in urban neighborhoods, fewer new units are built relative to the size of the housing stock. Limited construction holds back urban population growth and worsens urban affordability, even when—as rising prices show—housing demand in cities is strong. But what does the future hold?

Dreaming of the Suburbs and Beyond

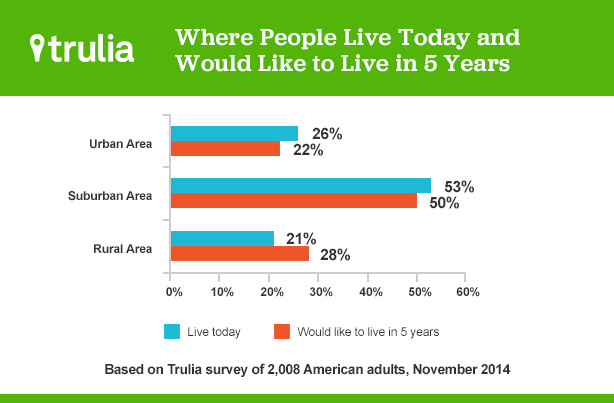

In November, Trulia asked more than 2,000 American adults whether they lived in an urban, suburban, or rural area, and where they wanted to live in five years. We didn’t define urban, suburban, and rural, but instead left them open to interpretation. (See note.) Rural areas were the winner. Just 21% of respondents said they were rural residents, but 28% said they would like to be living in a rural area in five years.

Urban residents feel the tug of the suburbs. For every 10 suburbanites who said they wanted to live in an urban area in five years, 16 urban dwellers said they wished to live in the suburbs. Even among young adults aged 18-34— who are more likely to live in urban areas than older adults are—more wanted to move from city to suburbs than the other way around, though the sample size was small.

To put it another way: Urban residents were the least likely to want to live in a similar area in five years. Two-thirds (67%) of urbanites wanted to live in an urban area in five years, compared with 80% of suburbanites and 83% of rural residents who wanted to live in areas like where they were.

Urban living generally declines with age, which partly explains why people are less likely to want to live in cities in five years. But will the large millennial generation give urban areas a sustained boost? In other words, will the U.S. population’s changing age profile be a tailwind or headwind for cities?

The Demographic Urban Headwind

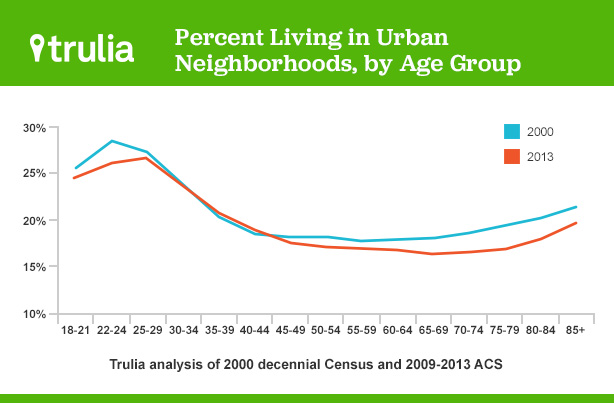

Today, urban neighborhoods are getting a demographic jolt. The largest segment of the big millennial group—folks in their early 20s—are entering the peak age for urban living. Some 26% of 22-24 year-olds live in urban neighborhoods, rising to 27% for 25-29 year-olds. Older people are far less likely to live in urban neighborhoods. Just 17% of the largest segment of baby boomers—those in their early 50s—live in such neighborhoods, a third lower than the share of early twentysomethings.

Comparing the 2009-2013 period with 2000, city living held up for people aged 25-44. Meanwhile, the share of adults 18-24 living in urban neighborhoods declined because they became more likely to live with their parents. But the most dramatic change in urban demographics concerned older adults. People age 45 and older were less likely to live in urban neighborhoods in 2009-2013 than in 2000. And the share of seniors in their 70s and early 80s living in urban neighborhoods fell more than 10 percent. In fact, for decades, seniors have become more likely to live in single-family homes. Increasingly, cities may be for the young. But that’s because oldsters are getting less urban, not because youngsters are getting more so.

What then will happen as the two largest groups age—those in their early 20s and those in their early 50s? As millennials get older, many will follow a familiar path: They’ll partner up, have kids, and move to the suburbs. Urban living starts to decline after ages 25-29 and drops to its lowest level at ages 65-69. On the other hand, the baby boomer leading edge is nudging 70, when urban living starts to rise again. The return of older boomers to cities will offset some of the millennial suburban migration.

Nevertheless, the aging population is overall a slight headwind for cities. Suppose the propensity of each age group for urban living remains at 2009-2013 levels. In that case, over the next few decades, the changing age distribution projected by the Census Bureau would lead to a slow, but steady decline in the share of adults living in urban neighborhoods. To be sure, the decline will probably be small—around a tenth of a percentage point per decade. Still, it suggests that aging boomers returning to cities might not fill all the homes suburbanizing millennials leave behind.

What could boost urban growth? For starters, more construction in city neighborhoods. That would allow higher urban population growth, while slowing price increases. Also, higher energy prices would encourage people to live closer to work and in smaller homes. By the same token, the recent drop in oil prices, if sustained, would have the opposite effect, becoming yet another tailwind for suburbs and headwind for cities. Finally, cultural attitudes could shift in favor of renting and urban living. But is that likely? Today, the vast majority of young renters aspire to own. Homeownership remains core to the American Dream. The future of the suburbs looks bright.

Notes:

To compare “city” versus “suburb,” we classify neighborhoods as urban or suburban based on how dense or spread out the housing is, as we have done in previous Trulia Trends posts. Using Census data, we define urban neighborhoods as ZIP codes (technically, ZCTAs — ZIP Code Tabulation Areas) where a majority of the housing is apartments, attached townhouses, or other multi-unit buildings; suburban neighborhoods are those where a majority of the housing is single-family detached houses. We used this methodology rather than simply identifying the biggest city in a metro as “urban” and treating the rest of the metro as the “suburbs,” as other reports on cities-versus-suburbs often do. The problem with using city boundaries is that many neighborhoods outside of the biggest city are actually much more urban than some neighborhoods within a city’s boundary. For instance, our definition classifies Hoboken, NJ, Central Square in Cambridge, MA, and Santa Monica – which are all very dense – as urban neighborhoods, even though they’re outside the city boundaries of New York, Boston, and Los Angeles, respectively.

The urban vs. suburban comparisons of prices and population growth cover the 100 largest metros, with individual ZIP codes classified as urban or suburban. Price changes are year-end year-over-year changes in median asking price per square foot of homes listed on Trulia. Population changes are the year-end year-over-year change in the U.S. Postal Service’s count of addresses receiving mail, reported monthly by ZIP code.

The consumer data is based on a survey of 2,008 American adults conducted for Trulia on November 6-10, 2014, by Harris Interactive. Respondents were asked whether they lived in an urban, suburban, or rural area, without being provided a definition. Self-reported urban locations aligned better with our housing-stock-based definition of urban versus suburban than with official city boundaries, though race, for instance, had a statistically significant relationship with self-reported neighborhood urban classification, even after accounting for the housing stock, household density, and city population.

Data on urban residence by age group is based on the ZCTA population as reported in the 2000 decennial Census and the 2013 five-year American Community Survey, covering the years 2009–2013. Population projections by single year of age from 2014 to 2060 are also from the Census Bureau.