When evaluating a potential new home, have you ever wondered how and why land parcels are sized the way they are? Or, even perhaps why your neighbor’s parcel is wider in the back and narrower in the front, while yours is a perfect rectangle? This process of defining property lines falls to the critical science and profession of surveying, and surveying your property is critical to ensuring a number of things, including saving you money and potential heartache in the future. It’s also important to us at Trulia.

As outlined in our “Relevancy Challenges” post, public records are a major piece of the content we deal with every day at Trulia, and a major driver in public records is land surveying. Land parcel data gives us the ability to generate rich data visualizations, accurate valuation models, and other decision-making capabilities for our users. In this post, I’ll give you a better sense of how surveying in the U.S. works.

Surveyors can measure pretty much anything on Earth – land, sky, and ocean beds – and ensure land parcels are correctly demarcated. Typically, they utilize three primary land surveying systems in the U.S.: Metes and Bounds and Public Land Survey System (PLSS) followed by Platted descriptions (save for some parts of the Louisiana Purchase).

Metes and Bounds

Some states that were part of the original 13 colonies utilize Metes and Bounds, a system which originated in the U.K. and describes land using local geographical features in combination with directions and distances. For example, a land parcel in such a system is described using prose such as:

“Beginning 330 feet south of the N 1/4 post of Section 36, T19N, R2E, thence South 165 feet, thence running West along highway 264 feet, thence North 165 feet, thence East 264 feet back to the point of beginning, containing 1 acre.” [1]

This system has some challenges though. For instance, irregular shaped properties have extremely complex descriptions and, over time, erosion can cause geographical features to move (streams) or die (trees). Moreover, while still used in the original 13 colonies today, the Metes and Bounds system was too complicated to handle land ownership in the acquired Western territories (roughly 75 percent) of the U.S.

PLSS

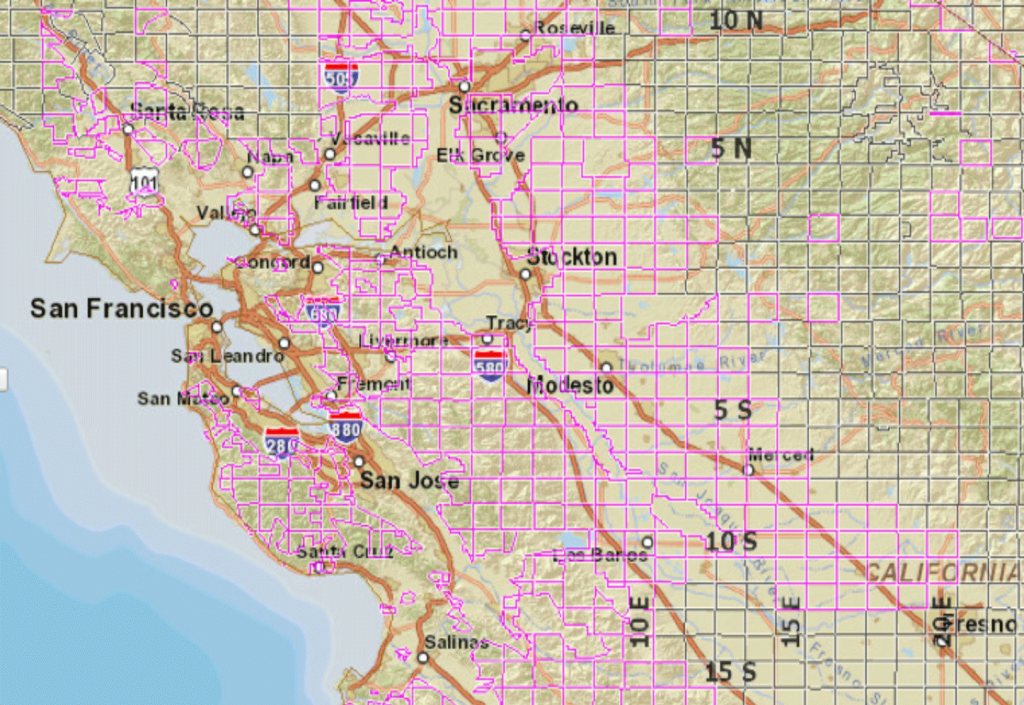

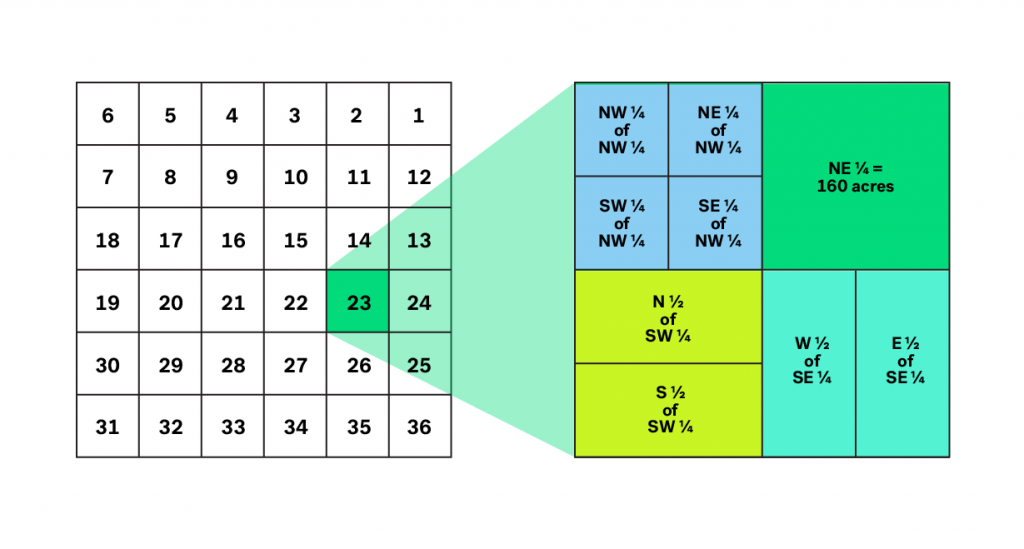

PLSS began with the Land Ordinance of 1785. It divides all land in the U.S. into six-by-six mile rectangles, or townships (Figure 1). Each township is then divided into 36 one-by-one mile sections (Figure 2). A description of a PLSS survey might read:

“The North-East one-quarter of the North-West one-quarter of Section 23, Township 21 North, Range 2 East.”

This denotes a 36-square mile geographical township that is located 120 miles (20 townships x six miles) North and six miles (one range x six miles) East of the initial point where the principal meridian and base line intersect. A township search tool can be found here.

Following this, Section 23 is located within the referenced geographical township. Each section in a township is further divided into quarter or half sections as illustrated in Figure 2. Thus, one would locate the North-West one-quarter (which is the first quadrant and is a quarter of the section) followed by the North-East one-quarter within this quadrant. This is the smallest unit of land description in our specified example for the PLSS system.

![Figure 1: Various PLSS townships around the Bay Area. Data was generated using the BLM GeoCommunicator [2].](https://wp.zillowstatic.com/trulia/wp-content/uploads/sites/1/2015/11/blog_0001_Layer-Comp-2-1024x705.png)

Figure 1: Various PLSS townships around the Bay Area. Data was generated using the BLM GeoCommunicator [2].

Figure 2: A typical township and sections. Section 1 in each township is in the northeast corner and subsequent sections follow a back and forth order and terminate with Section 36 in the southwest corner. The subdivisions within Section 23 are shown on the right.

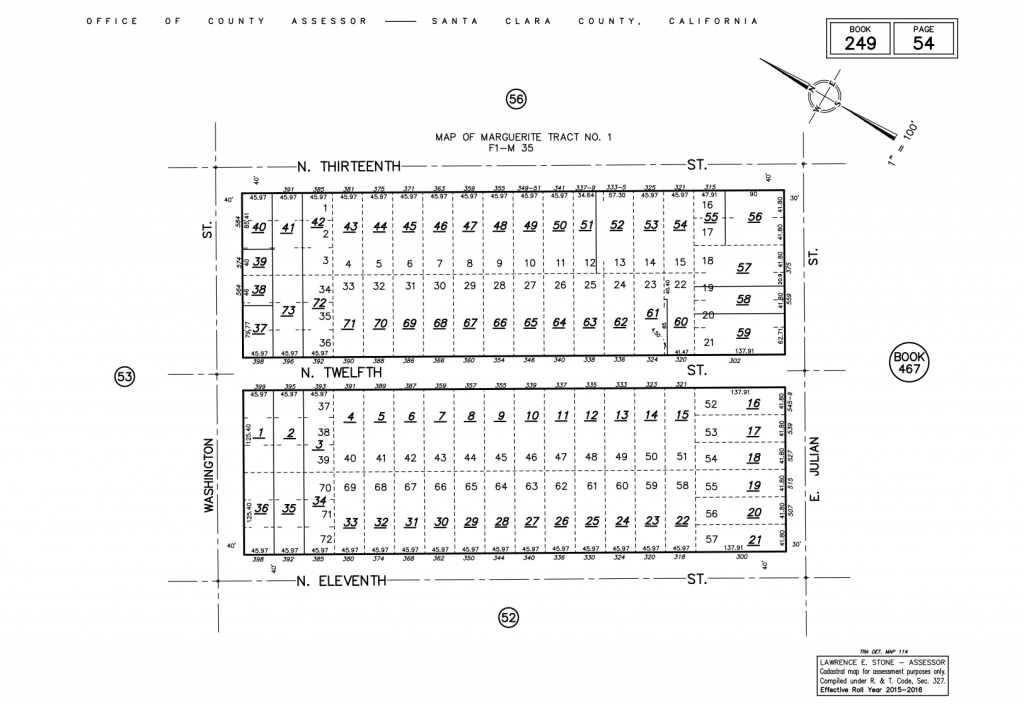

Platting

Finally, after using PLSS or Metes and Bounds, a survey is subdivided into smaller subdivisions, each of which is typically described using a Plat map (Figure 3). A Plat map is drawn to scale and shows individual lots, dimensions, area, etc. Each lot in a Plat is referenced using a specific lot number and subdivision name, or using a lot, block and reference to the Plat map. Parcels may be described as: “Lot 70 of Marguerite Tract No. 1 plat as record in Map Book 249, Page 54 of the Santa Clara County records.” Additionally, parcels are also assigned with an APN (Assessor Parcel Number), which typically is composed of an Assessor Book, Page and the individual lot number in this scheme.

Figure 3: A plat map of Marguerite Tract No. 1 in Santa Clara county, California. An APN for each property is generated by a combination of the Assessor Book Number, Assessor Page Number and the individual parcel number. All homes in this plat map will be of form 249-54-*

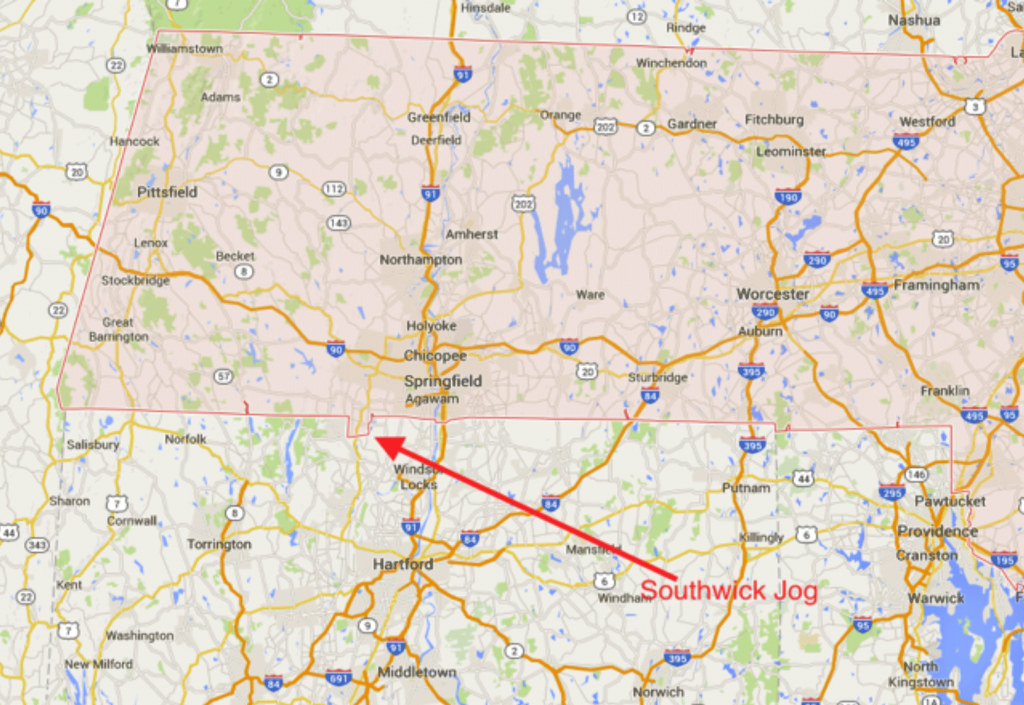

Beyond the business value for companies like Trulia, surveying property is very important for homeowners, as mentioned above. Surveying marks parcels that are recognized by the government, which you can then legally own, lease or rent, and yearly assessments of a parcel determine how much property tax you pay. Moreover, not paying attention to surveying can turn out to be quite expensive, especially if homes are built partially or completely on wrong lots. And mistakes can create quite a headache. Figure 4 shows a border anomaly between Massachusetts and Connecticut, where Connecticut literally lost a piece of itself to Massachusetts.

Needless to say, don’t skimp on surveying.

Figure 4: The Southwick Jog

Citations:

[1]http://www.michigan.gov/documents/treasury/State_Tax_Commission_Legal_Descriptions_Course_346936_7.pdf

[2] http://www.geocommunicator.gov/blmMap/Map.jsp?MAP=OG